- Home

- Sharon M. Draper

Blended Page 2

Blended Read online

Page 2

He’s a red neck. I don’t mean that in a negative way. But he seriously has a sunburn-red neck. He keeps sun block on the kitchen counter and slathers it on each morning before he leaves the house. He keeps his hair cut short, so there really is no protection for his poor neck. I’d never met a person who really had skin like that, one of those people who fry at the beach—honest! He’s the only guy I know who cooks like a Pop-Tart in the sun, but he’s pretty cool. He laughs a lot, loves to sing, blushes a lot, is a little overweight, and I’ve never seen him in a bad mood. He’s got dozens of interesting tattoos—it’s fun to “read” his arms during the summer when he wears short-sleeved shirts.

When he gets in his truck, he turns the country-western station up as loud as it will go, then sings along with folks like Willie Nelson and Garth Brooks. He says he likes the oldies, whatever that means.

He really likes my mom.

CHAPTER 7

Exchange Day

IT’S SUNDAY. I hate Sundays. I hate, hate, hate them. Even when I’m a wrinkled old lady, Sunday will always remind me of a worn, gray fake-leather sofa at the mall. It’s where Dad sits to wait for me when it’s his turn for custody for the week. Mom waits on the same couch on the opposite week. The stupid sofa never changes—just the faces of the grown-ups who come to claim me. I’m pretty sure my parents hate Sundays too.

Today, Dad waits stiffly, tapping his fingers, like he can’t relax until this is over. Probably true! He is never late. Anastasia sits beside him. She, at least, is smiling. Her shoes and purse are probably real leather—very fancy looking. She’s dressed in an amber-tone wool suit that’s almost the same color she is. Probably took her hours to do her face and hair. I touch the fuzzy frizz I call mine; it’s bushed out of the scrunchie. Again.

But today I break into a wide smile as Mom and I approach them, because Anastasia’s son, Darren, has come with them. He’s . . . well, not to sound like a fan girl, but he’s totally cool. He knows how to dress so he looks really sharp without looking like he worked at it, and he’s got a gravelly sounding voice that makes my friends get all kinds of silly.

I glance back guiltily at Mom, who is pale and tired looking, trying to scrape a stain off her Waffle House uniform with her fingernail. John Mark, in his favorite blue bowling shirt, walks on the other side of me. They’re speed-walking because we are late. Again. I wonder if other people are watching us, like we’re some kind of reality TV show. The caption would read: “Chocolate family meets vanilla family in the artificial reality that is a mall. Caramel daughter caught helplessly between the two.”

When we get to the sofa, Mom simply nods curtly at my father and Anastasia, gives me a forehead kiss, then turns and hurries away with John Mark. Dad nods as well. No need to exchange words, just me. They’ve got that head-nodding thing down to a science.

Now he hops up and I step into his outstretched arms. “What’s up, my Bella Isabella?” He smooths my hair. He’s been calling me that since I was little—it’s from a picture book that I used to make him read to me over and over. I couldn’t believe that someone had written about a girl—a warrior princess—with my name. I still have that book.

“I’m great, Daddy,” I tell him, then I quickly let go and grab Darren’s arm.

“I’m so glad you came today! What’s up?”

“I decided to witness the exchanging of the captive,” he teases, grabbing my backpack and slinging it over his shoulder. “Besides, I had to get my phone fixed.”

“How’s Aleeesha?” I ask, my turn to tease. “I hardly saw you the last time I was there.”

“If you must know,” he says, poking me in the arm, “Alicia is so very yesterday! I’m working up the courage to ask Monique to the dance next week.”

“I bet she’s checking her phone every hour in case you text!”

“Maybe,” he says, his voice a mystery.

“Still living up there on the honor roll?”

“Is there anywhere else?” He rolls his eyes.

“How’s Miss Pearson at the homeless shelter?”

“Still passing out mashed potatoes, blankets, and goody bags.”

“I’ve got some of those little lotion and shampoo bottles in my bag for her,” I tell him. “I saw them at CVS on sale for fifty cents each the other day, so I bought a bunch to help Miss Pearson out.”

“You’re the best, Izzy.”

“I know!” I tell him as I play punch him in the side.

Here’s the scoop on Darren. He’s totally awesome. In addition to volunteering at the homeless shelter, he gets grades that land him on the honor roll every quarter. He runs the fastest 100-meter dash on the track team. He’s got a boatload of colleges writing him letters, asking him to consider their university. They are asking him. Yeah, pretty impressive.

Best thing? He buys me ice cream every time I ask, even if it’s before dinner. Like I said—he’s the total package.

I go to Anastasia next and give her a hug as well. She’s a good hugger—it feels real, not faked. She smells like Shalimar—it’s a fancy French perfume I’ve learned to really like.

“So good to see you again, Isabella,” she murmurs. “I’ve missed you.” And she means it.

CHAPTER 8

Mom’s Week

WHIPLASH. THAT’S WHAT it feels like when I’m on a ride at the amusement park and it stops real fast. Last summer, Mom took me to the Hamilton County Fair. I loved it—the Tilt-A-Whirl and the Dragon Tail and the Racing Rollers—coasters on a double track! Best Saturday ever!

Then it was over. Like this week—I’m at Mom’s. I feel comfy when I’m here. Then the week is over. And I’m with Dad. I gotta get comfortable again in another house with different food and clothes and rules and stuff. It gets to be a pain. A weekly whiplash.

At least I don’t have to change schools every time. Lakeview Mountain School is halfway between my parents’ houses. There is no lake nearby, no mountain, no view of anything much except houses and apartment buildings. It’s big—we’ve got grades five through eight. Fifth graders look like scared little mice at the beginning of the school year. Did I look like that last year? They grow up to be eighth graders who remind me of sumo wrestlers, but we know to keep out of their way.

I like the cafeteria, though. They’ve tried to set it up so it almost looks like a real restaurant, and the food is only half bad. Today I plop my stuff next to Heather and Imani, who are already munching away.

“What’s up, girl?” Imani asks.

“Nothin’,” I reply as I grab one of her chips. Imani is tall and slim and dark, like some kind of African princess from a movie. She wears her hair in an Afro on purpose. It’s neat and black and perfectly round. Mine, on the other hand, is thick and frizzy with brownish-gold strands that can escape from every scrunchie ever made. The hair spray that can hold it down has not yet been invented. Yeah. Lucky me.

Imani dances ballet. She’s really limber and can fold herself into something that looks like a pretzel. When she walks, it’s almost like she glides. Boys trail behind her in silence and gawk. She ignores them.

Nobody looks at me like that.

Heather, with hair I can only describe as tangerine colored (I’m for real), once told me she thought her hair made her look like she was wearing a pizza. “Ick,” I’d told her. “Give yourself some credit, girl. You’re a fashion flame!”

“Hey, I like that,” she’d replied, faking a runway pose.

Heather usually brown-bags her lunch—her mom insists on packing healthy stuff like apples and carrot sticks. But as I look at the spaghetti goo I picked up from the food line, her lunch looks pretty good. And we always end up sharing whatever chips Imani brings.

After lunch we take our time leaving the cafeteria before heading to English class, where Mr. Kazilly awaits.

As we pass a table full of sixth-grade boys, I throw out there, in a low voice, “Have you ever seen anybody with eyes as green as Clint Hammond’s?”

“Or a fac

e as goofy as Logan Lindquist’s?” Heather adds. She makes fun of him, but I know she’s scrawled his name over and over and over again on the last page of her English notebook. Capital L is her favorite letter.

Heather boldly bumps into their table, jiggling it. The boys look up, then pretend they didn’t. I turn around just in time to see Logan toss a french fry right at us. It lands in Heather’s hair.

She pulls it out and cracks up. She does not throw it away, I notice.

Toby Smythe, who, by the way, is wearing a sleeveless athletic jersey even though it’s the middle of January, raises both his arms in the air, makes a stupid roaring noise, then sits back down. His buddies, including Clint and Logan, give him high fives.

Now we act like we didn’t see anything. But as soon as we get into the hall, Heather says, “Ew—did you see Toby’s got long, dangly underarm hair?”

Imani nods. “Totally gross.”

“Clint is still the cutest,” I say shyly.

“For sure,” Imani agrees. “Best-looking, uh, white boy in the sixth grade.”

I’m not sure what to say to that, but she and I kinda look at each other. Of course I know that Clint is white. I’ve just never thought about it, him being white. I swallow hard.

Then Heather adds, “Except for maybe . . .”

“Logan Lindquist!” we all say in unison.

CHAPTER 9

Mom’s Week

MR. KAZILLY, WHO teaches us both English and history, is a certified crazy man, at least in our opinion. He wears UGGs every day—even in the summer. I bet his feet totally stink at the end of the day!

His clothes are, well, let me describe them. He wears stuff like maroon capes and turquoise slacks, or stiff-collared button-down shirts with pinstripes. He’s got huge muscles, and he boasts about how he works out at the gym after school. He’s one of those people who might get noticed by a fashion magazine, maybe under the category of “Distinctive Teacher Style” or in an athletic magazine under the heading “Teachers with Six-Packs.” He likes colors—he calls them “hues”—so he might wear lavender and chartreuse together, partly for fashion, but I swear he dresses funky so we can have new vocabulary words.

Word. The man is a vocab freak. Ha, ha—get it? Word—vocabulary? Never mind. Anyway. This week’s words? A bunch of ordinary ones, like “mischief” and “possibility,” but he threw two cool ones in there: “collywobbles” and “gardyloo.”

Logan Lindquist raises his hand. “Why we ever gonna need words like this?” he asks.

“To broaden your language skills,” Mr. K. says in that reasonable, patient teacher voice.

Without missing a beat, Logan hollers, “I’m feeling kinda collywobbles, sir. I gotta hurl!” He runs to the garbage can, picks it up, and pretends to gag and vomit.

Of course the class cracks up.

And, of course, Mr. Kazilly is not amused. He opens his mouth to shut Logan up, when Logan suddenly hollers, “Gardyloo!” and slings the contents of the wastebasket across the front of the room. Balled-up papers and potato chip wrappers and empty juice boxes fly everywhere!

Chaos. Shock. Laughter.

Logan gets an hour of detention. “Totally worth it!” he says with an arm pump to his friend Toby of the Hairy Armpits. In Logan’s defense, I’m sure none of us will ever forget the meaning of those two words.

When Mr. Kazilly tells us our homework assignment, however, he’s got me wanting to shout “gardyloo” and chuck the wastebasket across the room. We have to write an essay called “The Real Me.”

Heather and Imani both raise their hands. They always ask the questions I haven’t got the nerve to.

Mr. Kazilly nods toward Heather. She gets called on all the time.

“So why do we have to write this now?” she asks in her most polite-for-the-teacher voice. “This seems more like a getting-to-know-you paper for, like, when school first starts in the fall.”

I shrink in my seat, just in case the teacher decides to blow fire from his nostrils like a dragon.

But he’s cool with the question. “I want each of you to consider your personal identity as we begin the new year. Each of you is uniquely wonderful. I want you to think about that as you write.” He’s, like, beaming as he says this. I bet he spent his whole holiday vacation thinking this one up.

Heather gives me the you gotta be kidding me bug-eye. I cover my mouth to keep from laughing.

“Your paper is due on Monday,” Mr. Kazilly says. “At least four paragraphs.” The whole class groans, but he’s good at ignoring us. He never gets around to calling on Imani.

For me, I gotta remember that I’ll start the essay at Mom’s house and turn it in while I’m at Dad’s.

This assignment totally sucks. The real me? I have no idea who that is. Especially since there’s pretty much two of me.

CHAPTER 10

Mom’s Week

The Real Me

My name is Isabella Badia Thornton. Isabella is an awesome name—it flows like the music of a waterfall. I gotta admit, though, when I think of a character in a book named Isabella, she’s tall, got blue eyes, and has long, flowing pale-gold hair. Well, actually, that kinda describes my mom.

But that blue-eyed princess is so not me. My skin is kinda bronze-colored, I guess. I’m not real tall, my eyes are a deep green color, and my hair is wild and kinky—and kind of a dirty brown. If I’m reading a book about a girl named Isabella, I figure at some point she’s going to walk on a golden sandy beach where the wind is blowing so that her perfect blond hair can “billow in the breeze.” I’ve read that line in stories. Clearly, none of those writers have met me. Or my hair. Ha!

My father gave me the middle name Badia. It’s African, and it means “unique” or “unprecedented.” I like that. He told me that he and Mom had their first argument on the day I was born. She didn’t want me to be “bogged down” by what she called “some crazy African name,” but Dad insisted. And he was right—when I say my middle name out loud, it lifts me up. I stand a little taller. When I’m a famous pianist, I’ll make sure the name written in fancy script on the program says my full name—Isabella Badia Thornton. It is who I am.

CHAPTER 11

Dad’s Week

MY FATHER, ISAIAH Maxwell Thornton III, landed a position as a lawyer at the biggest bank in town when he moved back. He specializes in complicated banking cases—“investment banking,” I’ve heard him say. I’m not exactly sure what that means, but I do know all the money he deals with belongs to somebody else. I figure he must be good at his job, though, because he always has a lot of cash to spend on me.

He drives a brand-new black Mercedes with all the frills. Man, that car sure does smell good! The seats are so soft they sorta hug you. We never eat french fries in Dad’s car.

He likes to dress up. Three-piece suits. Crisp white button-downs. Cuff links that match his ties. Buttoned down and buttoned up—that’s my dad. I feel like he’s more comfortable dressed like that. He once wore a suit when we went bowling. No joke. I made him take off the tie and the jacket and roll up his sleeves.

“This isn’t the opera, Daddy—why are you always so proper?” I asked him when he picked me up from school one day.

He gave me a look, but he loosened his tie. “I thought we might stop by Target,” he said instead. “I know you like that place, and you might want to get a T-shirt or some jeans or something.”

“Yeah, that would be cool,” I told him. “But you gotta learn to chill, Dad. Maybe you can get something like ordinary clothes for yourself while we’re there. You look like you’re the president of the company or something!” I gave him the sad sad sad headshake. So he completely took off the tie. But he couldn’t bring himself to wrinkle his shirt by rolling up the sleeves. Pitiful.

Mom, on the other hand, has a dozen pairs of leggings, three well-worn pairs of jeans, and probably a million cool T-shirts. She likes shirts that have clever sayings. Last week she wore one that said, “Teach your kids about

taxes—eat 30% of their ice cream!” They always make me laugh.

Dad will wear a shirt without a collar, and even jeans on weekends, but he sends them to the cleaner’s, so there’s a crease down the center of each leg, like Sunday pants. Yep. Pitiful times two.

“And by the way, Daddy, you gotta stop ironing your jeans! Nobody does that!” I told him as we walked from the car toward the giant red circle Target sign. He just laughed.

Then he looked at my torn, frayed jeans. “And you think those are a fashion statement?” he asked, smirking.

“Yep. They even sell them here. And they’re not cheap!” I reminded him with a laugh of my own.

“Hmm. You look . . . impoverished.”

“And that’s bad?”

“For my daughter, yeah.” His face grew serious. “Here’s the thing. I think it’s important we look our very best at all times.”

“We, like you and me?” I asked, even though I knew what he really meant.

He sucked his breath in slowly. “No, Isabella. Like us, like people of color, like Black folks. That we.”

I cocked my head. “Why?”

It took him a few clicks before he finally said, “The world looks at Black people differently. It’s not fair, but it’s true.”

I was already aware of this, but I didn’t think Dad had ever been so direct about it. Mom for sure would never have had this conversation with me.

So I flat out asked: “Does the world look at me that way?”

He answered without hesitation. “Yes.”

“But what about the Mom half of me?”

“To me, that’s probably the best half of you, the part that makes you smart and funny and lovable and just plain cute!” he told me with a big smile. “But it has nothing to do with skin color or race. And everything to do with the flavor of Kool-Aid you turned out to be. You understanding what I’m sayin’?”

The Birthday Storm

The Birthday Storm November Blues

November Blues The Backyard Animal Show

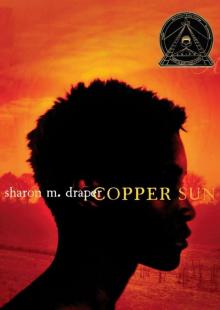

The Backyard Animal Show Copper Sun

Copper Sun Romiette and Julio

Romiette and Julio The Sassy Collection

The Sassy Collection Stars and Sparks on Stage

Stars and Sparks on Stage The Battle of Jericho

The Battle of Jericho Tears of a Tiger

Tears of a Tiger The Dazzle Disaster Dinner Party

The Dazzle Disaster Dinner Party Just Another Hero

Just Another Hero Forged by Fire

Forged by Fire The Buried Bones Mystery

The Buried Bones Mystery Out of My Mind

Out of My Mind Stella by Starlight

Stella by Starlight Panic

Panic Darkness Before Dawn

Darkness Before Dawn The Space Mission Adventure

The Space Mission Adventure Double Dutch

Double Dutch Shadows of Caesar's Creek

Shadows of Caesar's Creek