- Home

- Sharon M. Draper

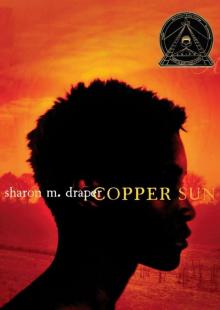

Copper Sun

Copper Sun Read online

COPPER SUN

Also by Sharon M. Draper

Tears of a Tiger

Forged by Fire

Darkness Before Dawn

Romiette and Julio

Double Dutch

The Battle of Jericho

November Blues

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

SIMON PULSE

An imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2006 by Sharon M. Draper

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON PULSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Also available in an Atheneum Books for Young Readers hardcover edition.

Designed by Sonia Chaghatzbanian

The text of this book was set in Life.

First Simon Pulse edition January 2008

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Draper, Sharon M. (Sharon Mills)

Copper sun / Sharon M. Draper.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Two fifteen-year-old girls—one a slave and the other an indentured servant—escape their Carolina plantation and try to make their way to Fort Mose, Florida, a Spanish colony that gives sanctuary to slaves.

ISBN-13: 978-0-689-82181-3 (hc)

ISBN-10: 0-689-82181-6 (hc)

[1. Slavery—Fiction. 2. Indentured servants—Fiction. 3. South Carolina—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600–1775—Fiction. 4. Florida—History—Spanish colony, 1565–1763—Fiction. 5. African Americans—History—18th century—Fiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.D78325Cop 2006

[Fic]—dc22

2005005540

ISBN-13: 978-1-4169-5348-7 (pbk)

ISBN-10: 1-4169-5348-5 (pbk)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4391-1511-4 (ebook)

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Part One: Amari

Chapter 1: Amari and Besa

Chapter 2: Strangers and Death

Chapter 3: Sorrow and Shackles

Chapter 4: Death March to Cape Coast

Chapter 5: The Door of No Return

Chapter 6: From Sand To Ship

Chapter 7: Ship of Death

Chapter 8: Toward The Edge of The World

Chapter 9: Lessons—Painful and Otherwise

Chapter 10: The Middle Passage

Chapter 11: Land Ho

Chapter 12: Welcome to Sullivan’s Island

Chapter 13: The Slave Auction

Part Two: Polly

Chapter 14: The Slave Sale

Chapter 15: Polly and Clay

Chapter 16: Teenie and Tidbit

Part Three: Amari

Chapter 17: Amari and Adjustments

Chapter 18: Roots and Dirt

Chapter 19: Peaches and Memories

Chapter 20: Isabelle Derby

Part Four: Polly

Chapter 21: Rice and Snakes

Chapter 22: Lashed With a Whip

Part Five: Amari

Chapter 23: Flery Pain and Healinc Hands

Chapter 24: Gator Bait

Part Six: Polly

Chapter 25: Birth of The Baby

Chapter 26: Facing Mr. Derby

Chapter 27: Death in the Dust

Chapter 28: Punishment

Chapter 29: Locked in the Smokehouse

Chapter 30: Tidbit’s Farewell

Part Seven: Amari

Chapter 31: The Doctor’s Choice

Chapter 32: The Journey Begins

Chapter 33: Deep in the Forest

Chapter 34: Lost Hush Puppy

Chapter 35: Dirt and Clay

Part Eight: Polly

Chapter 36: Should We Trust Him?

Part Nine: Amari

Chapter 37: Lost and Found and Lost

Part Ten: Polly

Chapter 38: The Spanish Soldier

Part Eleven: Amari

Chapter 39: Crossing The River

Chapter 40: Time To Meet The Future

Chapter 41: Fort Mose

Chapter 42: Copper Sun

Afterword

A Reading Group

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I am the granddaughter of a slave.

My grandfather—not my great-great-grandfather or some long-distant relative—was born a slave in the year 1860 on a farm in North Carolina. He did not become free until the end of the Civil War, when he was five years old.

Hugh Mills lived a very long life, married four times, and fathered twenty-one children. The last child to be born was my father. Hugh was sixty-four years old when my father was born in 1924.

I dedicate this book to him, and to my grandmother Estelle, who, even though she was not allowed to finish school, kept a written journal of her life. It is one of my greatest treasures. One day I hope to write her story.

I also dedicate this to all those who came before me—the untold multitudes who were taken as slaves and brought to this country, the millions who died during that process, as well as those who lived, suffered, and endured.

Amari carries their spirit. She carries mine as well.

HERITAGE

BY COUNTEE CULLEN

What is Africa to me:

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

Women from whose loins I sprang

When the birds of Eden sang?

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me?

COPPER SUN

IN SPITE OF THE HEAT, AMARI TREMBLED.The buyers of slaves had arrived. She and the other women were stripped naked. Amari bit her lip, determined not to cry. But she couldn’t stop herself from screaming out as her arms were wrenched behind her back and tied. A searing pain shot up through her shoulders. A white man clamped shackles on her ankles, rubbing his hands up her legs as he did. Amari tensed and tried to jerk away, but the chains were too tight. She could not hold back the tears. It was the summer of her fifteenth year, and this day she wanted to die.

Amari shuffled in the dirt as she was led into the yard and up onto a raised wooden table, which she realized gave the people in the yard a perfect view of the women who were to be sold. She looked at the faces in the sea of pink-skinned people who stood around pointing at the captives and jabbering in their language as each of the slaves was described. She looked for pity or even understanding but found nothing except cool stares. They looked at her as if she were a cow for sale. She saw a few white women fanning themselves and whispering in the ears of welldressed men—their husbands, she supposed. Most of the people in the crowd were men; however, she did see a poorly dressed white girl about her own age standing near a wagon. The girl had a sullen look on her face, and she seemed to be the only person not interested in what was going on at the slave sale.

Amari looked up at a seabird flying above and remembered her little brother. I wish he could have flown that night, Amari thought sadly. I wish I could have flown away as well.

PART ONE

AMARI

1. AMARI AND BESA

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING UP THERE, KWASI?” Amari asked her eight-year-old brother with a laugh. He had his legs wrapped around the trunk of the top of a co

conut tree.

“For once I want to look a giraffe in the eye!” he shouted. “I wish to ask her what she has seen in her travels.”

“What kind of warrior speaks to giraffes?” Amari teased. She loved listening to her brother’s tales—everything was an adventure to him.

“A wise one,” he replied mysteriously, “one who can see who is coming down the path to our village.”

“Well, you look like a little monkey. Since you’re up there, grab a coconut for Mother, but come down before you hurt yourself.”

Kwasi scrambled down and tossed the coconut at his sister. “You should thank me, Amari, for my treetop adventure!” He grinned mischievously.

“Why?” she asked.

“I saw Besa walking through the forest, heading this way! I have seen how you tremble like a dove when he is near.”

“You are the one who will be trembling if you do not get that coconut to Mother right away! And take her a few papayas and a pineapple as well. It will please her, and we shall have a delicious treat tonight.” Amari could still smell the sweetness of the pineapple her mother had cut from its rough skin and sliced for the breakfast meal that morning.

Kwasi snatched back the coconut and ran off then, laughing and making kissing noises as he chanted, “Besa my love, Besa my love, Besa my love!” Amari pretended to chase him, but as soon as he was out of sight, she reached down into the small stream that flowed near Kwasi’s tree and splashed water on her face.

Her village, Ziavi, lay just beyond the red dirt path down which Kwasi had disappeared. She headed there, walking leisurely, with just the slightest awareness of a certain new roundness to her hips and smoothness to her gait as she waited for Besa to catch up with her.

Amari loved the rusty brown dirt of Ziavi. The path, hard-packed from thousands of bare feet that had trod on it for decades, was flanked on both sides by fat, fruit-laden mango trees, the sweet smell of which always seemed to welcome her home. Ahead she could see the thatched roofs of the homes of her people, smoky cooking fires, and a chicken or two, scratching in the dirt.

She chuckled as she watched Tirza, a young woman about her own age, chasing one of her family’s goats once again. That goat hated to be milked and always found a way to run off right at milking time. Tirza’s mother had threatened several times to make stew of the hardheaded animal. Tirza waved at Amari, then dove after the goat, who had galloped into the undergrowth. Several of the old women, sitting in front of their huts soaking up sunshine, cackled with amusement.

To the left and apart from the other shelters in the village stood the home of the chief elder. It was larger than most, made of sturdy wood and bamboo, with thick thatch made from palm leaves making up the roof. The chief elder’s two wives chattered cheerfully together as they pounded cassava fufu for his evening meal. Amari called out to them as she passed and bowed with respect.

She knew that she and her mother would soon be preparing the fufu for their own meal. She looked forward to the task—they would take turns pounding the vegetable into a wooden bowl with a stick almost as tall as Amari. Most of the time they got into such a good rhythm that her mother started tapping her feet and doing little dance steps as they worked. That always made Amari laugh.

Although Amari knew Besa was approaching, she pretended not to see him until he touched her shoulder. She turned quickly and, acting surprised, called out his name. “Besa!” Just seeing his face made her grin. He was much taller than she was, and she had to stand on tiptoe to look into his face. He had an odd little birthmark on his cheek—right at the place where his face dimpled into a smile. She thought it looked a little like a pineapple, but it disappeared as he smiled widely at the sight of her. He took her small brown hands into his large ones, and she felt as delicate as one of the little birds that Kwasi liked to catch and release.

“My lovely Amari,” he greeted her. “How goes your day?” His deep voice made her tremble.

“Better, now that you are here,” she replied. Amari and Besa had been formally betrothed to each other last year. They would be allowed to marry in another year. For now they simply enjoyed the mystery and pleasure of stolen moments such as this.

“I cannot stay and talk with you right now,” Besa told her. “I have seen strangers in the forest, and I must tell the council of elders right away.”

Amari looked intently at his face and realized he was worried. “What tribe are they from?” she asked with concern.

“I do not think the Creator made a tribe such as these creatures. They have skin the color of goat’s milk.” Besa frowned and ran to find the chief.

As she watched Besa rush off, an uncomfortable feeling filled Amari. The sunny pleasantness of the afternoon had suddenly turned dark. She hurried home to tell her family what she had learned. Her mother and Esi, a recently married friend, sat on the ground, spinning cotton threads for yarn. Their fingers flew as they chatted together, the pale fibers stretching and uncurling into threads for what would become kente cloth. Amari loved her tribe’s design of animal figures and bold shapes. Tomorrow the women would dye the yarn, and when it was ready, her father, a master weaver, would create the strips of treasured fabric on his loom. Amari never tired of watching the magical rhythm of movement and color. Amari’s mother looked up at her daughter warmly.

“You should be helping us make this yarn, my daughter,” her mother chided gently.

“I’m sorry, Mother, it’s just that I’d so much rather weave like father. Spinning makes my fingertips hurt.” Amari had often imagined new patterns for the cloth, and longed to join the men at the long looms, but girls were forbidden to do so.

Her mother looked aghast. “Be content with woman’s work, child. It is enough.”

“I will help you with the dyes tomorrow,” Amari promised halfheartedly. She avoided her mother’s look of mild disapproval. “Besides, I was helping Kwasi gather fruit,” Amari said, changing the subject.

Kwasi, sitting in the dirt trying to catch a grasshopper, looked up and said with a smirk, “I think she was more interested in making love-dove faces with Besa than making yarn with you!” When Amari reached out to grab him, he darted out of her reach, giggling.

“Your sister, even though she avoids the work, is a skilled spinner and will be a skilled wife. She needs practice in learning both, my son,” their mother said with a smile. “Now disappear into the dust for a moment!” Kwasi ran off then, laughing as he chased the grasshopper, his bare feet barely skimming the dusty ground.

Amari knew her mother could tell by just the tilt of her smile or a fraction of a frown how she was feeling. “And how goes it with young Besa?” her mother asked quietly.

“Besa said that a band of unusual-looking strangers are coming this way, Mother,” Amari informed her. “He seemed uneasy and went to tell the village elders.”

“We must welcome our guests, then, Amari. We would never judge people simply by how they looked—that would be uncivilized,” her mother told her. “Let us prepare for a celebration.” Esi picked up her basket of cotton and, with a quick wave, headed home to make her own preparations.

Amari knew her mother was right and began to help her make plans for the arrival of the guests. They pounded fufu, made garden egg stew from eggplant and dried fish, and gathered more bananas, mangoes, and papayas.

“Will we have a dance and celebration for the guests, Mother?” she asked hopefully. “And Father’s storytelling?”

“Your father and the rest of the elders will decide, but I’m sure the visit of such strangers will be cause for much festivity.” Amari smiled with anticipation, for her mother was known as one of the most talented dancers in the Ewe tribe. Her mother continued, “Your father loves to have tales to tell and new stories to gather—this night will provide both.”

Amari and her mother scurried around their small dwelling, rolling up the sleeping mats and sweeping the dirt floor with a broom made of branches. Throughout the village, the pungent smells of goat s

tew and peanut soup, along with waves of papaya and honeysuckle that wafted through the air, made Amari feel hungry as well as excited. The air was fragrant with hope and possibility.

2. STRANGERS AND DEATH

THE STRANGERS WHOM BESA HAD SPOKEN OF arrived about an hour later. Everyone in the village came out of their houses to see the astonishing sight—pale, unhealthy-looking men who carried large bundles and unusual-looking sticks as they marched into the center of the village. In spite of the welcoming greetings and looks of excitement on the faces of the villagers, the strangers did not smile. They smelled of danger, Amari thought as one of them looked at her. He had eyes the color of the sky. She shuddered.

However, the unusual-looking men were accompanied by warriors from the Ashanti tribe, men of her own land, men her people had known and traded with, so even if the village elders were concerned, it would be unacceptable not to show hospitality. Surely the Ashanti would explain. But good manners came first.

Any occasion for visitors was a cause for excitement, so after the initial amazement and curiosity at the strange men, the village bubbled with anticipation as preparations were made for a formal welcoming ceremony. Amari stayed in the shadows, watching it all, uneasy, but not sure why.

Their chief, or Awoamefia, who could be spoken to only through a member of the council of elders, invited the guests to sit, and they were formally welcomed with wine and prayers. The chief and the council of elders, made up of both men and women, were always chosen for their wisdom and made all the important decisions. Amari was proud that her father, Komla, was one of the elders. He was also the village storyteller, and she loved to watch the expressions on his face as he acted out the stories she had heard since childhood.

“We welcome you,” the chief began. “Let your yes be yes and your no be no. May you be protected from evil, and may you live to a ripe old age. If you come in peace, we receive you in peace. Heroism is the dignity of our ancestors, and, in their name, we welcome you.” He passed the wine, made from palm tree leaves, to Amari’s father, then to the other elders, and finally to the strangers.

The Birthday Storm

The Birthday Storm November Blues

November Blues The Backyard Animal Show

The Backyard Animal Show Copper Sun

Copper Sun Romiette and Julio

Romiette and Julio The Sassy Collection

The Sassy Collection Stars and Sparks on Stage

Stars and Sparks on Stage The Battle of Jericho

The Battle of Jericho Tears of a Tiger

Tears of a Tiger The Dazzle Disaster Dinner Party

The Dazzle Disaster Dinner Party Just Another Hero

Just Another Hero Forged by Fire

Forged by Fire The Buried Bones Mystery

The Buried Bones Mystery Out of My Mind

Out of My Mind Stella by Starlight

Stella by Starlight Panic

Panic Darkness Before Dawn

Darkness Before Dawn The Space Mission Adventure

The Space Mission Adventure Double Dutch

Double Dutch Shadows of Caesar's Creek

Shadows of Caesar's Creek